Back to the Future—

New York's Lost Transit Legacy

Page 3

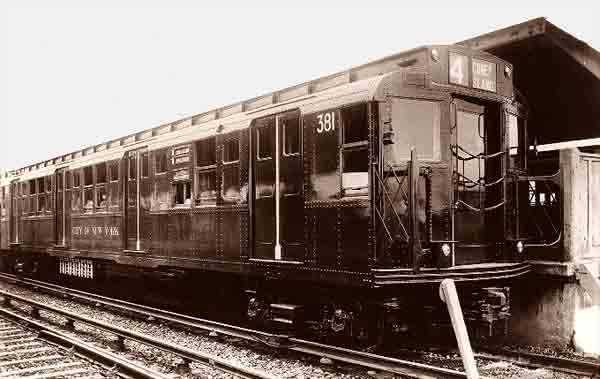

Sturdy but blandly

utilitarian ,

the IND bought more than 1700 of these R1-9 subway cars. Borrowing

liberallly from the BMT's 1925 Triplex design, it

set the conservative tone for New York City subway design for decades

after the end of the BMT. This view is at Coney Island where car 381 and others

were tested in revenue service on the BMT's Sea Beach Line from July to

November, 1931, before the IND opened. Paul Matus

Collection

The Nation’s

Transit Leader

By the late 1920s, with the BMT and IRT systems

mostly in place, the IND system being built and additional private

streetcar and bus lines blanketing its streets, New York City was the

center of mass transit in the U.S., as it still is today. One difference

between the 1920s and our new century is that mass transit in general, and

rail transit in particular, was a vibrant and mostly free enterprise

industry.

The leader in this giant industry

was New York’s BMT. What the IRT and IND lacked the BMT had in abundance:

a vision of transit as an attractive product, and the passenger as a

customer.

The subway equipment was made of

steel and was new as far as rapid transit equipment went (most around a

decade old or less), but the elevated fleets included wooden equipment

from the turn of the century and earlier. These wooden cars presented a

double problem: safety considerations, including fire and

crash-worthiness, led to the removal of wooden equipment from subway

tunnels, while the older elevated structures were incapable of handling

heavier but safer steel cars.

The IRT’s

solution was a non-solution: its own subway lines and the elevated lines

it leased from the Manhattan Railways were virtually separate systems,

with some interoperation at the far reaches of the system in the Bronx and

Queens. It made only incremental changes to its elevated equipment, such

as the fitting of doors to cars that previously used labor-intensive gates

for access.

The City’s cure was worse than the disease for the private

companies. Its IND undermined the private companies, both literally and

figuratively, by building subways to compete with the elevated lines. For

example, the 8th Avenue subway competed head-to-head with the IRT’s

9th Avenue el, and the Fulton Street

subway competed with the BMT’s bread-and-butter Fulton Street

Line.

This subway replacement option was not

within the private company’s reach as the IND, then being constructed

strictly from the public purse, did not worry much about the market at

all. This was to result in a magnificently engineered system that was

sometimes overbuilt. An ambitious “second system” was proposed in 1929 but

the first system had already ballooned New York City’s rapid transit

debt.

The BMT not only had a large elevated system, but one which

was much more tightly integrated with its subway system. It had no elevateds in

Manhattan, as the IRT did, to bring its elevated line passengers to the heart

of the City. It knew that, with the IND getting the City’s construction money,

future capital construction would be limited. The BMT had ambitions—it wanted

to tie its Fulton Street Line to its subway system at DeKalb Avenue. It wanted

to bring subway service to the farther reaches of its system. It wanted to

eliminate the dangers of steel and wooden equipment operating on the same

tracks. And it didn’t want to upgrade its elevated fleet with

patchwork solutions. It wanted to replace the fleet with the most modern

equipment in the country, but how?

In 1927 the Transit

Commission, which could rule on the suitability of equipment to run on the

City’s rapid transit lines, appointed a committee of engineers to

determine the feasibility of constructing a steel car light enough to

operate on the older elevated lines. After thorough study, they decided

such a car was not feasible.

Continued on page

4

|

The Bluebird used advanced

controls. Both acceleration and braking was regulated by

this Cineston controller from General Electric.

Paul Matus

Collection |

The Third Rail and The Third Rail

logo are trademarks of The Composing Stack Inc.

|